The Nightingale

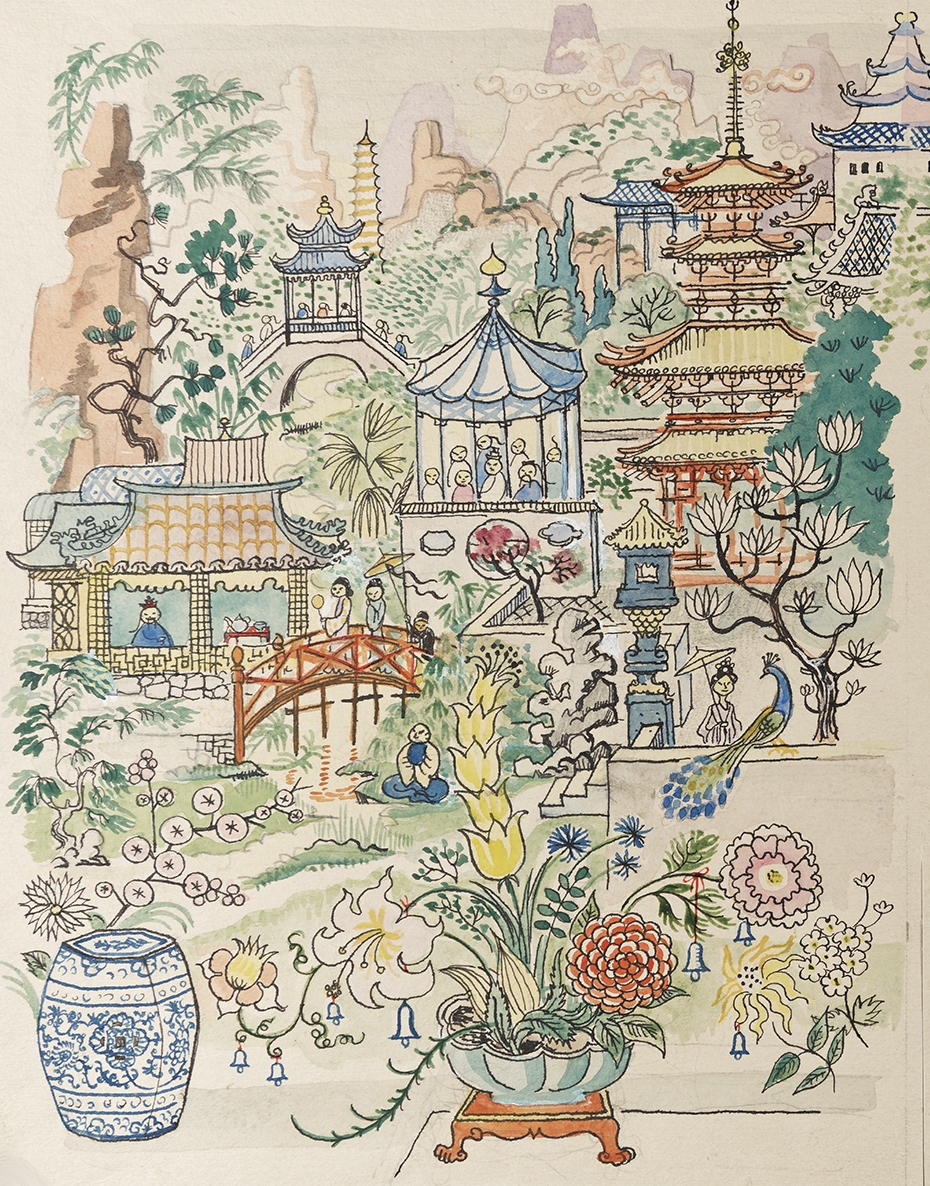

In China, as you well know, the emperor is Chinese, and all those he has around him are Chinese. All this took place many years ago, but that is exactly why it’s worth hearing the story before it gets forgotten! The emperor’s palace was the most magnificent in all the world made entirely of fine porcelain, so precious, but so fragile, and to be handled so delicately that great care had to be taken. In the garden one could see the most wonderful flowers, and around the most magnificent silver bells had been tied that would tinkle, so that one would not pass without noticing the flower. Yes, everything was so carefully thought out in the emperor’s garden, and it stretched so far that not even the gardener knew where it ended; if one kept on walking, one would enter the loveliest wood with tall trees and deep lakes. The wood dropped right down to the sea, which was blue and deep – large ships could sail directly under the branches, and in these there lived a nightingale that sang so wonderfully that even the poor fisherman, who had so many other things to take care of, lay quite still and listened when he was out on the water at night to take up his nets and then heard the nightingale. ‘Heavens above, how beautiful it is!’ he said, but then he had other things to do and forgot the bird; although the following night, when it sang once more and the fisherman was out there, he immediately said. ‘Heavens above, how beautiful it is!’

Travellers from every country in the world came to the emperor’s city, and they admired it, the palace and the garden, but when they got to hear the nightingale, all of them said: ‘But this is the best thing even so!’

And the travellers told people about it when they arrived back home, and the scholars wrote many books about the city, the palace and the garden, but they did not forget the nightingale, it was given pride of place; and those who were able to write poetry wrote the loveliest poems that were all about the nightingale in the wood down by the deep sea.

Those books went all round the world, and some of them eventually came to the emperor. He sat in his golden chair, read and read, nodding with his head at every moment, for it pleased him to hear the wonderful accounts of the city, the palace and the garden. ‘But the nightingale is the very best thing even so!’ stood written there.

‘What’s this!’ the emperor said, ‘the nightingale! I don’t know anything about it! Is there such a bird in my empire – and in my garden, what’s more! I’ve never heard about that! do I have to read about it to find out such a thing!’

And he called his lord-in-waiting, who was of such high rank that if anyone less distinguished dared to address him, or ask him about anything, the only answer he would give was ‘P’, which means nothing whatsoever.

‘There is said to be a quite remarkable bird here called a nightingale!’ the emperor said, ‘and it is said to be the very best thing in my great empire! why hasn’t anyone ever said anything about it to me!’

‘I’ve never heard it mentioned before!’ the lord-in-waiting said, ‘It’s never been presented at court!’ –

‘I wish to have it come here this evening and sing for me!’ the emperor said. ‘The rest of world knows all about what I have, and I don’t know it myself!’

‘I’ve never heard it mentioned before!’ the lord-in-waiting said, ‘I will seek it out, I will find it!’ –

But where was it to be found? The lord-in-waiting ran up and down all the staircases, through the halls and corridors, none of those he met had ever heard any mention of the nightingale, and the lord-in-waiting ran back to the emperor and said that it was in all likelihood a fable made up by those who wrote books. ‘Your imperial Majesty must not believe what people write! It is pure fabrication and something that is called black magic!’

‘But the book I read about it in,’ the emperor said, ‘has been sent me by the mighty emperor of Japan, and so it cannot be untrue. I wish to hear the nightingale! it is to be here this evening! it has my highest favour! and if it does not come, everyone at court will be punched in the stomach after they have eaten dinner.’ ‘Tsing-pi!’ the lord-in-waiting said, and ran again up and down all the staircases, through all the halls and corridors; and half the court ran with him, for they were not at all keen to be punched in the stomach. There were questions asked everywhere about the strange nightingale that the whole world knew about, but nobody at court.

Finally, they found a poor little girl in the kitchens, who said: ‘Oh, good heavens, the nightingale! I know it well! And yes, how it can sing! every evening I am allowed to take a few leftovers from the table home to my poor sick mother, she lives down by the shore, and on my way back, when I am tired and rest in the wood, I hear the nightingale sing! It brings tears to my eyes, it is as if my mother kissed me!’

‘Little kitchen-girl!’ the lord-in-waiting said, ‘I shall get her a permanent appointment in the kitchen and permission to see the emperor eat if she can lead us to the nightingale, for it has been summoned to the court this very evening!’ –

And then they all set off to the wood where the nightingale usually sang – half the court went along. As they were well on their way, a cow started to bellow.

‘Oh!’ said the gentlemen of the court, ‘there we have it! but what a remarkable power in such a small creature! I’m sure I have heard it before!’

‘No, that’s the cows bellowing!’ the little kitchen-girl said, ‘we’re still quite a way from the right place!’

Now the frogs quacked in the marsh.

‘Delightful!’ the Chinese court chaplain said, ‘now I can hear her, it’s like small church bells!’

‘No, that’s the frogs!’ the little kitchen-girl. ‘But I think we will hear it soon!’

Then the nightingale started to sing.

‘That’s the one,’ the little girl said, ‘listen! listen! and it’s sitting right there!’ and she pointed to a small, grey bird up in the branches.

‘How is it possible?’ said the lord-in-waiting, ‘that was never how I had imagined it! how plain it looks! it must have lost its colour at the sight of so many distinguished persons!’

‘Little nightingale!’ the little kitchen-girl called out quite loudly, ‘our gracious emperor wants so much for you to sing for him!’

‘With the greatest of pleasure!’ the nightingale said and sang so it was a joy to hear it.

‘It is like glass bells!’ the lord-in-waiting said, ‘ and see how it uses its little throat! it’s very strange we haven’t heard it before! it will be a great success at court!’

‘Shall I sing once more for the emperor?’ the nightingale asked, who thought the emperor was with them.

‘My excellent little nightingale!’ the lord-in-waiting said, ‘I have the great pleasure to summon you to a court function this evening, at which you will enchant his high imperial Grace with your charming singing!’

‘It’s best heard out in nature!’ the nightingale said, but it was willing to follow them even so, when it heard that the emperor so desired.

Everything had been really shined and polished at the palace! Walls and floors made of porcelain gleamed in the light of many thousands of gold lamps! the loveliest flowers that could tinkle properly were placed in the corridors; there was much toing and froing and a draught, but precisely that made all the bells on the flowers tinkle – one couldn’t hear oneself speak.

In the middle of the great hall, where the emperor sat, a golden perch had been set up, and the nightingale was to sit on it; the whole court was there, and the little kitchen-girl had been given permission to stand behind the door, as she now had the title of a real kitchen-girl. Everyone was in their best finery, and they all looked at the little grey bird, which the emperor nodded to.

And the nightingale sang so delightfully that the emperor had tears in his eyes, the tears rolled down his cheeks, and then the nightingale sang even more beautifully, its song went straight to the heart; and the emperor was so pleased and said that the nightingale was to have his golden slipper to wear round its throat. But the nightingale declined, it had already been rewarded enough.

‘I have seen tears in the eyes of the emperor and that is my dearest treasure! the tears of an emperor have a remarkable power! God knows I have been sufficiently rewarded!’ and then it sang once more with its sweet, wonderful voice.

‘That is the most lovable coquetry I know!’ the ladies standing there said, and they put water in their mouths so they could cluck when people spoke to them; they thought that they were nightingales too; yes, even the footmen and chambermaid expressed their satisfaction, and that is saying a great deal, for they are the most difficult of persons to please. Yes indeed, the nightingale was a great success!

It was now to stay at the court, have its own cage, and be allowed to take a walk twice a day and once at night. It was given twelve servants, who each had a silk ribbon attached to its leg and they kept a tight hold. There was nothing pleasurable about that walk.

The whole city talked about the remarkable bird, and if two people met each other, one would say nothing except ‘night-’ and the other ‘-gale’ and they would sigh and understand each other, eleven pork butcher’s children were even named after it, though not one of them had a musical note in its body.–

One day, a large package arrived for the emperor on which was written: Nightingale.

‘Ah, here is a new book about our famous bird!’ the emperor said; but it wasn’t a book, it was a small piece of craftsmanship that lay in a box, a mechanical nightingale that was to resemble the living one, but that was completely studded with diamonds, rubies and sapphires; as soon as one wound the mechanical bird up, it could sing one of the tunes the real one sang, and then its tail went up and down and glinted with silver and gold. Round its neck there hung a small ribbon which stated: ‘The nightingale of the Emperor of Japan is poor compared with that of the Emperor of China.’

‘How delightful!’ they all said, and the person who had brought the mechanical bird was immediately given the title of superior-emperor-nightingale-bringer.

‘Now they must sing together! what a duet it will be!’

And so they had to sing together, but it didn’t really work all that well, for the real nightingale sang in its own way, and the mechanical bird ran on small cylinders – ‘it’s not its fault in any way,’ the music master said, ‘it keeps time particularly well and exactly as I would have instructed it!’ Then the mechanical bird was to sing on its own. – It was just as great a success as the real one, and what was more was much prettier to look at: it glittered like bracelets and brooches.

It sang the same piece thirty-three times and was not tired in spite of this; people would have liked to have heard it from the beginning again, but the emperor felt that now the live nightingale was to sing a little – – but where was it? no one had noticed that it had flown out of the open window, off to its green woods.

‘But what’s all this!’ the emperor said; and all his courtiers scolded and maintained that the nightingale was a most ungrateful creature. ‘But we’ve still got the best bird!’ they said, and the mechanical bird had to sing yet again, and it was the thirty-fourth time they got the same tune, but they didn’t know all of it quite yet, for it was so difficult, and the music master praised the bird so lavishly, he asserted that it was better than the real nightingale, not only as regards apparel and the many lovely diamonds, but also for its inner qualities.

‘For you see, ladies and gentlemen – and above all the emperor! – one can never calculate in advance with the real nightingale what is going to come, but with the mechanical bird everything has been decided beforehand! that is how it will be and nothing else! one can account for it, one can open it up and show the underlying human thought, how the cylinders are organised, how they are running, and how the one follows the other!’ –

‘Exactly what I was thinking,’ they all said, and the music master was given permission, the following Sunday, to present the bird to the people; they were also to hear it sing, the emperor said; and they heard it, and were as contented as if they had got merry on tea-water – for that is just a Chinese thing to do – and all of them said ‘oh’ and stuck in the air the finger that is called ‘lickapot’, and all of them nodded; but the poor fishermen who had heard the real nightingale said: ‘It sounds beautiful enough, and it sounds quite like it, but there’s something missing, though I don’t know what!’

The real nightingale had been banished from both country and realm.

The mechanical bird had its place on a silk cushion close to the emperor’s bed; all the presents it had been given, gold and precious stones, lay round it, and its title had risen to ‘high-imperial-bedside-table-singer, number one rank on the left-hand side’, because the emperor regarded that side as being the finer, the one on which the heart sits – and the heart also sits on the left in an emperor. And the music master wrote twenty-five volumes about the mechanical bird, it was so learned and long and with the most difficult Chinese words in them, so everyone said that they had read and understood them, for otherwise they would have been stupid and been punched in the stomach.

A whole year passed in this way: the emperor, the court and all the Chinese knew every little cluck in the mechanical bird’s song by heart, but they preferred it precisely for that reason; they could sing along too, and they did. The street urchins sang ‘zizizi! cluckcluckcluck!’ and the emperor sang it too – it really was most delightful!

One evening, however, while the mechanical bird was in full song, and the emperor lay in his bed listening to it, something went ‘woosh!’ inside the bird – something broke: ‘Whirrrr!’ all the wheels span round, and the music stopped.

The emperor immediately jumped out of bed and had his royal physician called, but what help was that! so he had the watchmaker called, and after much discussing and examining he managed to get the bird reasonably in working order, but he said that it must be used very sparingly, for the spikes were so worn and it was impossible to replace them with new ones and be sure the music was right. What great sadness that caused! they only dared let the mechanical bird sing once a year, and that was bad enough; but the music master then gave a little speech with all the difficult words in it and said that everything was just as good, as before, and then everything was just as good as before.

Five years had now passed, and a heavy blow caused the whole country to grieve, for deep down they all held their emperor in great affection, he was now ill and could not live long, people said, a new emperor had already been chosen and people stood out in the street and asked the gentleman-in-waiting how things were with their emperor.

‘P!’ he said and shook his head.

The emperor lay cold and pale in his large, magnificent bed, all the court thought he was dead, and they all went off to greet the new emperor; the valets all went outside to talk about it, and the palace maid-servants held a large coffee party. Cloth was laid out in all the halls and corridors, so that people’s footsteps were muffled, so it was so quiet, so quiet. But the emperor was not yet dead; he lay stiff and pale in the magnificent bed with the long velvet curtains and the heavy gold tassels; high up, a window was open, and the moon shone in on the emperor and the mechanical bird.

The poor emperor could hardly breathe, it was as if something heavy lay on his chest; he opened his eyes, and then he saw that it was Death who was sitting on his chest and had put his gold crown on, and in one hand he held the emperor’s golden sword, and in the other his splendid banner, and everywhere in the folds of the great velvet bed-curtains strange heads poked out, some extremely ugly, others wonderfully gentle: it was the emperor’s evil and good deeds that gazed on him, now that Death was sitting on his heart:

‘Do you remember that?’ one after the other whispered. ‘Do you remember that!’ and then they told him so much that sweat broke out on his brow.

‘I never knew that!’ the emperor said; ‘music, music, the great Chinese drum!’ he shouted, ‘so I don’t have to listen to everything they say!’

And they kept on, and Death nodded like a Chinese at everything which was being said.

‘Music, music!’ the emperor shouted. ‘You wonderful small golden bird! go on, sing, sing! I have given you gold and precious gifts, I’ve hung my gold slipper round your neck myself, go on, sing, sing!’

But the bird stood still, there was no one to wind it up, and without that it couldn’t sing; but Death went on gazing at the emperor with his large, empty eye sockets, and it was so quiet, so frightfully quiet.

Then suddenly, close to the window, the loveliest song could be heard: it was the little, live nightingale sitting on a branch outside; it had heard of the emperor’s plight, so it had come to give him consolation and hope with its song; and the more it sang, the paler the figures around him grew, the blood flowed more and more rapidly in the emperor’s weak limbs, and Death itself listened and said: ‘Keep singing, little nightingale! keep singing!’

‘Yes, if you give me that magnificent gold sword! yes, if you give me that fine banner! if you give me the emperor’s crown!’

And Death gave up each of the treasures for a song, and the nightingale still kept on singing, and it sang of the quiet churchyard where the white roses grow, where the elder tree smells so sweetly, and where the fresh grass is watered by the tears of grieving relatives; then Death started to long for his garden and he floated, like a cold, white mist, out of the window.

‘Thank you, thank you!’ the emperor said, ‘you heavenly little bird, I know you for sure! You I have chased from my country and realm! yet despite this you have sung the evil visions away from my bed, lifted Death from my heart! How can I repay you?’

‘You have repaid me!’ the nightingale said, ‘I got tears from your eyes the first time I sang, I will never forget you for that! those are the jewels that gladden a singer’s heart! – but sleep now, and grow well and strong! I shall sing for you!’

And it sang – and the emperor fell into a sweet sleep, a sleep so mild and refreshing.

The sun was shining in through the windows to him when he awoke, strengthened and healthy; none of his servants had returned yet, for they thought he was dead, but the nightingale was still sitting there singing.

‘You must stay with me always!’ the emperor said, ‘you are only to sing when you wish to yourself, and I will smash the mechanical bird into a thousand pieces.’

‘Do not do that!’ the nightingale said. ‘it has done all the good it was able to! keep it as always! I cannot reside here at the palace, but let me come whenever I want to, and I will sit on a branch there by the window in the evening and sing for you, so that you can become both glad and thoughtful! I will sing to you about those who are happy, and about those who suffer! I will sing about good and evil that is kept hidden around you! the little songbird flies far and wide to the poor fisherman, the farmer’s roof, to everyone who is far away from you and your court! I love your heart more than your crown, though the crown has a scent of something sacred about it! – I will come, I will sing for you! – but one thing you must promise me!’ –

– ‘Anything at all!’ the emperor said, and he stood there in his imperial costume, which he had put on himself and held his sword, which was heavy with gold, up against his heart.

‘One thing I ask of you! tell no one that you have a small bird that tells you everything, then things will go even better!’

And with that the nightingale flew away.

The servants came in to see their dead emperor; – – yes, there they all stood, and the emperor said: ‘Good morning!’

Refer to the work

Hans Christian Andersen: The Nightingale. Translated by John Irons, edited by Jacob Bøggild & Mads Sohl Jessen. Published by The Hans Christian Andersen Centre, University of Southern Denmark, Odense. Version 1.0. Published 2024-10-02. Digitized by Holger Berg for the website hcandersen.dk, version 1.0, 2024-10-02

This version of the text is published under the following license: Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0). Images are not included in this license and may be subject to copyright.