The Dryad

A Fairy Tale from the Time of the Exposition in Paris in 1867We’re on our way to the Paris Exposition.

Now we’re there! What speed, what swiftness, completely without magic; we travelled by steam, on water and on land.

Ours is the age of fairy tale.

We’re in the heart of Paris, at a large hotel. Flowers flank the entire staircase, with deep-pile carpets over the steps.

Our room is pleasant, the balcony door is open and overlooks a large square. Down below spring resides, it has reached Paris, arriving at the same time as us, and has come in the form of a large, young chestnut tree, with its large, fine new leaves, clad in full spring beauty that outdoes all the other trees on the square! one of which has definitively left the ranks of the living and lies uprooted, sprawling on the ground. Where it once stood a fresh chestnut tree will now be planted and will grow.

As yet it is still high up on the heavy wagon that has brought it to Paris this very morning from many miles away in the countryside. There it had stood for many years close to a mighty oak, under which the devout old priest often sat telling stories to the listening children. The young chestnut tree used to listen in too; the Dryad inside it was still only a child; she could recall the time when the tree was so small that it only stuck up slightly above the tall stems of grass and bracken. They were then as tall as they would ever be, but the tree grew taller for every year that passed, drank in air and sunshine, got dew and rain and, when necessary, was swayed and shaken by the strong winds. That is all part of its upbringing.

The Dryad was happy with her life and being alive, with the sunshine and birdsong, but what made her happiest of all was human voices, she understood their speech just as well as that of the animals.

Butterflies, dragonflies and flies, well, everything that could fly, used to pay her visits; all of them with the latest gossip: they had news of the village, the vineyard, the wood, the old castle with its park that had canals and ponds; down in the water livings creatures also lived that were able, in their fashion, to fly from place to place under water, creatures who possessed knowledge and powers of thought; they spoke not a word, they were that clever.

And the swallow, who had dived down into the water, spoke of the beautiful goldfish, of the plump bream, the portly tench and the old, moss-covered crucian carp. The swallow gave an excellent description, but it’s better to see for yourself, it said; but how on earth could the Dryad ever get to see such creatures! she had to make do with looking out over the lovely countryside and sensing the busy activity of human life.

That was nice enough, but nicest of all was when the old priest stood here under the oak tree and talked about France, of heroic deeds by men and women whose names are mentioned with admiration down through all ages.

The Dryad heard about the shepherd girl Joan of Arc, about Charlotte Corday, she heard about ancient times, about the time of Henry IV and Napoleon I, and right up until the present day, about ability and greatness; she heard names each of which re-echoed in people’s hearts: France is the world country, the fertile soil of genius with the vessel of liberty!

The village children listened attentively, the Dryad no less; she was a schoolchild along with the others. In the forms of the drifting clouds she saw one picture after the other of what she had been told.

The cloud-filled sky was her picture book.

She felt so happy in beautiful France, but even so had the feeling that the birds, that every creature that could fly, were far more privileged that she was. Even the fly could take a look around, far beyond the Dryad’s horizon.

France was so vast and wonderful, but she only saw a tiny fraction of it; it stretched out far and wide with its vineyards, woods and large cities, and of all these Paris was the most magnificent, the mightiest. The birds could reach it, but she never could.

Among the village children there was a little girl, so ragged, so poor, but a joy to behold; she always sang and laughed, and bound red flowers in her black hair.

‘Don’t ever go to Paris!’ the old priest said. ‘Poor child! If you ever to there, it will be the ruin of you!’

But she did, even so.

The Dryad often thought about her, they shared the same urge and longing for the great metropolis.

Spring, summer, autumn, winter came and went; a couple of years passed.

The Dryad’s chestnut tree came into flower for the first time, the birds chirped about this in the delightful sunshine Then a fine carriage came along the road with a distinguished lady driving the swift-footed beautiful horses herself; a dressed-up little jockey sat up behind her. The Dryad recognised her, the old priest recognised her, shook his head and said sadly:

‘So you went there even so! and it became the ruin of you, poor Mari!’

‘Should she be called poor!’ the Dryad thought to herself, ‘no, what a transformation! she’s dressed up like a countess! that took place in the enchanted city. Oh, if only I was there in all that magnificence and splendour! it even lights up the clouds at night when I look over to where I know the city lies.’

Yes, the Dryad used to gaze in that direction every evening, every night. She saw the gleaming mist on the horizon; she missed it in the bright, moonlit night; she missed the drifting clouds that showed her images from city and history.

The child reaches for its picture book, the Dryad reached for the cloud-world, her book of thoughts.

The sky, warm and cloud-free in summer, was an empty page to her, and now that was all she had had to look at for several days.

It was the height of summer, with sun-baked days with not a breath of air; every leaf, every flower lay as if in a doze, humans too.

Then clouds rose up over in the part of the horizon where at night the gleaming mist announced: here is Paris.

The clouds rose up, formed themselves into a complete land of mountains, burgeoned out through the air, out over the entire countryside, as far as the Dryad could see.

The clouds lay like huge blackish blue masses of rock stacked on top of each other high into the sky. The flashes of lightning shot out, ‘they too are servants of God Almighty,’ the old priest had said. And there was a bluish, dazzling flash, a gleam like that of the sun itself which blasted the boulders asunder. The lightning struck, cleaving the mighty old oak from top to toe, its crown was split, its trunk was split, it fell cleft in twain, as if spreading out to embrace the emissary of light.

No brass cannons are able to resound through the air out over the land at the birth of a royal child like the boom of the thunder at the passing of the old oak tree. The rain poured down, the refreshing breeze cleansed the air, the storm was over, it was like a festive Sunday. The villagers gathered round the old oak tree that had been laid low; the old priest spoke in praise of it, an artist painted the trees as a lasting memory.

‘Everything passes!’ the Dryad said, ‘passes away like the cloud does, never to return!’

The old priest no longer came here; the school roof had collapsed, the teacher’s desk was gone. The children did not come, but autumn came, winter came, but spring did so too, and throughout the passing seasons the Dryad continued to look in the direction where, every evening and night, far out on the horizon, Paris shone like a gleaming mist. Out of it flew locomotive upon locomotive, one railway train after the other, chasing each other, whizzing and whistling around the clock; in the evening, in the morning and in broad daylight came the trains, and out of each and into each thronged people from every country of the world; a new Wonder of the World had called them to Paris.

What form did this wonder take?

‘A magnificent flower of art and industry,’ they said, ‘has emerged through the barren sand of the Champ de Mars; a huge sunflower, from whose leaves one can learn Geography, Statistics, acquire the knowledge of government officials, be lifted up by Art and Poetry, learn about the size and greatness of countries.’ – ‘A fairytale flower,’ others said, ‘a multi-coloured lotus that spreads its green leaves out over the sand, like velvet carpets that have emerged in the early spring, the summer will see it in all its glory, the autumn gales will blow it away, not a leaf nor root will remain.’

Outside the École Militaire the Champ de Mars spreads out in a time of peace, the field without a blade of grass, an expanse of sand steppe hewn out of the African desert, where a fata morgana displays its rare castles in the air and hanging gardens; on the Champ de Mars they now stood, more magnificent, more marvellous, for through ingenuity they had become reality.

‘The present-day Aladdin’s castle has been erected!’ it was said, ‘day by day, hour by hour it reveals more of its sumptuous splendour. Its never-ending halls are resplendent with marble and colours. Here Master ‘Bloodless’ moves his limbs of steel and iron in the huge ring-hall of machines. Works of art made of metal, of stone, of woven materials announce the life of the spirit that moves in all countries of the world: halls of pictures, profusions of flowers, everything that mind and hand can create in the craftsman’s workshop is here on display; even ancient monuments from old castles and peat-bogs are present there.

The overwhelmingly large, diverse show has to be scaled down, squeezed into the size of a toy so that it can be reproduced, perceived and seen in its entirety.

The Champ de Mars, like a large Christmas spread, bore an Aladdin’s castle of industry and art, and around it were knick-knacks from every country: knick-knacks of greatness, each nation was granted a recollection of its home.

Here stood a pharaoh’s palace from Egypt, there a caravanserai of the desert; the Bedouin on his camel, coming from his land of sun, rushed past; here there were also Russian stables with fiery, magnificent steeds from the steppes; the small, thatched Danish peasant cottage stood there with its Danish flag close to Gustav Vasa’s magnificently carved wooden houses from Dalarna in Sweden; American cabins, British cottages, French pavilions, kiosks, churches and theatres lay strangely strewn around, and in the midst of all this, the fresh green lawns, the clear running water, flowering shrubs, rare trees, greenhouses where one imagined oneself transported to tropical forests; entire rose gardens, fetched from Damascus were resplendent under glass roofs, what colours, what a scent!

Caves of stalactites, artificially made, fringed small lakes of fresh and salt water, offered a view of the realm of fishes; one stood on the sea bed among fish and polyps.

All of this, they said, the Champ de Mars now has on offer, and over the whole expanse of this richly decked festive table the thronging crowds of people move like industrious swarms of ants, on foot or drawn in small carriages, not all legs can manage such a tiring walk.

Out here, from the early morning to late evening, they come. Steamer upon steamer, packed with passengers, glide down the Seine, the number of carriages is swiftly on the increase, the hosts of people on foot and on horseback grow more numerous, the trams and omnibuses are crammed, stuffed and adorned with people, all of these streams are moving towards a single goal: ‘The Paris Exposition!’ All the entrances are resplendent with the French flag, around the bazaar buildings of the various countries flutter the flags of all the nations; there is a humming and buzzing from the hall of the machines, carillons chime melodiously down from the towers, the organ is being played inside the churches; hoarse, snuffled singing mingles with it from oriental cafés. It is like a tower of Babel, a Babel-like tongue, a Wonder of the World.’

That is certainly how it was, how accounts of it were, who hadn’t heard them? The Dryad knew everything that had been said about ‘the new wonder’ in the city of cities.

‘Fly, you birds! fly there and see everything, come back and tell me everything!’ the Dryad begged.

Longing swelled into desire, became an all-consuming thought – and then: in the still, silent night, with a bright full moon, a spark flew out from its disc, the Dryad saw, one that fell, gleamed like a shooting star, and in front of the tree, the branches of which were tossed as if caught by a strong gust of wind, there stood a mighty, gleaming figure; it spoke in tones as gentle and strong as the trump of the Last Day that gives the kiss of life and pronounces sentence.

‘You shall enter the city of enchantment, you shall put down roots there, feel the surging currents, the air and the sunshine there. But it will mean that your life-span will be shortened, the number of years that awaited you here in the open air will be worn down in the city to a small sum of years. Poor Dryad, it will be the ruin of you! your longing will grow, your yearning, your craving will become stronger! The tree itself will become a prison to you, you will leave your natural sheath behind, leave your own nature, fly out and mix with humanity, and then your years will be reduced to half the life-span of a May fly, a single night only; your life will be extinguished, the leaves on the tree will wither and be blown away, never to return.’

So did it sound, so did it sing, and the light faded away, but not the longing and desire of the Dryad, she quivered expectantly, in a wild fever of excitement.

‘I will enter the city of cities!’ she cried out ecstatically, ‘life begins, swells like a cloud, no one knows where it is bound.’

At daybreak, when the moon grew pale and the clouds red, the hour of fulfilment came, the words of the promise came true.

People came with spades and poles, they dug round the roots of the tree, deep down, in under it; a wagon came up, drawn by horses, the tree with its roots and the great clod of earth around them was lifted, wrapped in rush mats, a nice, warm foot muff, and then placed on the wagon, secured with rope, for it was to off on its travels, to Paris, to grow and stay there in the metropolis of mighty France, the city of cities.

The branches and leaves of the chestnut tree quivered in the first moment of movement, the Dryad in the excitement of anticipation.

‘Away! away!’ said every pulse. ‘Away! away!’ rang out in quivering, hovering words. The Dryad forgot to say farewell to her native soil, to the swaying blades of grass and the innocent mayweeds that had looked up to her as to a grand lady in the Garden of Our Lord, a young princess playing at being a shepherdess out here in the open air.

The chestnut tree was on the wagon, it nodded with its branches, ‘goodbye’ or ‘away’, the Dryad did not know which, she was thinking of, dreaming of the wonderful new and yet so familiar life that was about to start. No childlike heart in innocent joy, no sensuous blood more brimming with thoughts has begun the journey to Paris.

‘Farewell!’ became ‘away! away!’

The wheels of the wagon turned, what was distant grew closer and was laid behind them; the countryside changed as the clouds do; new vineyards, woods, villages and gardens appeared, came into view, rolled past. The chestnut tree moved forward, the Dryad moved forward along with it. Locomotive upon locomotive rushed past each other; they sent up clouds that formed shapes that told of Paris, from where they were coming, to where the Dryad was travelling.

Everything around her knew and surely understood where she was travelling to; it seemed to her that every tree she passed, stretched out its branches towards her and asked her: ‘Take me with you! take me with you!’ In every tree there was of course a Dryad full of longing.

What a constant change of scenery! what swift flight! It was as if the houses shot up out of the earth, more and more of them, closer and closer to each other. The chimneys rose like flowerpots placed on top of each other and alongside each other on the roofs; large inscriptions with never-ending letters, figures painted on the walls from foundation to window-sills appeared.

‘Where does Paris start, and when will I be inside it?’ the Dryad wondered. The crowds of people increased, the hustle and bustled increased, carriage followed carriage, people on foot and on horseback, and around shop after shop, music, singing, shouting, talking.

The Dryad in her tree was in the heart of Paris.

The large, heavy wagon came to a halt on a small square planted with trees, surrounded by tall houses where every window had its own balcony; people from up there gazed down at the young, fresh chestnut tree that arrived on the wagon and was now going to be planted here instead of the tree that had died, been taken up and left lying on the ground. People stood still on the square and looked with a smile and with pleasure at the new tree in its springtime green; the older trees, still only in bud, bade her ‘welcome! welcome!’ with their sighing branches, and the fountain, which sent jets of water into the air and let them splash down into the large basin, let the wind carry drops over to the newly arrived tree, as if offering it a welcoming drink.

The Dryad sensed its tree being lifted down from the wagon and placed in its future position. The roots of the tree were hidden in the ground, fresh turf was laid on top; flowering shrubs and flowerpots with flowers in them were, like the tree, now planted; a whole patch of garden was established in the middle of the square. The dead, uprooted tree, killed by the gas-filled air, the kitchen-fire air and all the plant-stifling air of the city, was placed on the wagon and driven away. The crowd of people watched this, children and old folk sat on the bench in the open air and looked up through the leaves of the tree. And we who are relating all this stood on the balcony, looked down at the young spring foliage still full of fresh country air, and said as the old priest would have done: ‘Poor Dryad!’

‘I’m blissfully happy, blissfully happy!’ the Dryad said, ‘thought I cannot quite grasp or express what I feel, everything is as I had imagined! and yet not as I had imagined it would be!’

The houses were all so tall, so close; the sun only shone down fully on one wall, and it was covered in placards and posters, where people stood crowded together. Carriages rushed past, large and small; omnibuses, these overloaded houses on wheels, sped past, people on horseback shot by, carts and carriages for pleasure trips insisted on doing the same. Weren’t the high-grown houses standing so close, the Dryad wondered, about to move away, to change shape like the clouds in the sky were able to, to glide aside, so that she could look into Paris, out over it. Notre-Dame would have to show itself, the Vendôme Column and the Wonder of the World that had attracted and was attracting so many strangers to the city.

The houses didn’t budge an inch.

It was still day when the lamps were lit, the rays from the gaslights gleamed from the shops, could be seen through the branches of the tree; it was like summer sunshine. The stars above came out, the same that the Dryad had seen in her native soil; it seemed to her she could feel a breeze from there, so pure and mild. She felt herself uplifted, fortified, felt a strength of vision out to the very tips of each of the tree’s leaves, a feeling in the outermost tips of its roots. She felt herself in the world of living human beings, looked at by kindly eyes; around her was bustle and noise, colour and light.

From a side-street the sound of wind instruments and the foot-tapping tunes of hurdy-gurdies could be heard. Yes, time to dance! time to dance! to be happy and enjoy life, it seemed to say.

It was music that made people, horses, carriages, trees and houses have to dance to it, if they were able to dance. There was a sudden rush of joy in the Dryad’s breast.

‘How blissful and delightful!’ she cried out ecstatically. ‘I am in Paris!’

The next day, the night that followed it, and the day after that all offered the same spectacle, the same activity, the same life, always changing and yet always the same.

‘I now know every tree, every flower here on the square! I know every house, balcony and shop from my position in the small pent-up corner that conceals the great big city from me. Where are the triumphal arches, the boulevards and the Wonder of the World? I can see nothing of all this; cooped up as if in a cage I stand among the high houses that I now all know by heart with their inscriptions, posters, signs, all the dainty delicacies that no longer appeal to me. Where is all that I heard about, knew about, longed for and because of which I wanted to come here? What have I grasped, won, found! I long as before, I sense a life I must grasp and live in! I have to be in the streams of the living! frisk around there, fly like the birds, see and sense, become a whole person, grasp half a day of life for years of living in the tiredness and boredom of the everyday, where I languish, sink, fall like the meadow mist and disappear. I want to gleam like the cloud, gleam in the soul of life, look out across everything like the cloud, sail across the sky like it does, no one knows where!’

That was the Dryad’s sigh, which rose up as a prayer:

‘Take the years of my life, give me half of the life of a May fly! free me from my prison, give me a human life, human happiness for just a brief while, just this one single night if needs be, and then punish me only for my bold love of life, my longing for life! erase me, let my natural sheath, the fresh young tree then wither, be felled, become ashes, waft away on the wind!’

There was a rustling in the branches of the tree, a tickling sensation, a quivering in every leaf, as if fire ran through it or out from it, a gust of wind passed through the crown of the tree, and in the midst of all this, a female figure rose up, the Dryad herself. In an instant, she was sitting beneath the gas-lit, leafy branches, young and beautiful, like poor Mari, to whom it had been said: ‘the great city will be the ruin of you!’

The Dryad sat at the foot of the tree, by her front door, the one she had locked and then thrown away the key. So young, so beautiful! The stars saw her, the stars twinkled, the gas lamps saw her, gleamed, waved! how slender she was and yet so firm, a child and yet a fully grown young woman. Her dress was as fine as silk, green as the newly unfurled leaves in the crown of the trees; in her nut-brown hair hung a half-open chestnut blossom; she looked like the goddess of spring.

For just a brief minute she sat there motionless, then she sprang up, and with the rapidity of a gazelle she raced from the spot, was round the corner; she ran, she sprang, like the glinting of a mirror carried out into the sunshine, the glinting that at every moment is cast first here, then there; and if one had looked carefully and been able to see what there was to see, how wonderful it all would have been; everywhere where she paused for a moment, her dress, her form changed, according to the nature of the place, the house whose lamp illuminated her.

She reached the boulevard; here there was a shimmering ocean of light from gas flames in lanterns, shops and cafés. Here stood trees in rows, young and slender, each one hid its Dryad from the rays of artificial sunlight. The whole never-ending pavement was like one great reception room; here tables had been laid out with all kinds of refreshments, champagne, chartreuse, down to coffee and beer. Here there was a display of flowers, of pictures, statues, books and multi-coloured materials.

From the bustling crowd beneath the high houses she looked out over the frightening swift-flowing current just outside the row of trees: a raging river of rolling carriages, cabriolets, coaches, omnibuses, taxis, gentlemen on horseback and marching regiments. It meant risking life and limb to try and cross to the opposite bank. Now blue lights gleamed, then it was gas light that predominated, suddenly a rocket soared up, where from, where to?

Yes indeed, this was the great highway of the world metropolis!

Here was the sound of soft Italian melodies, there Spanish songs accompanied by the clacking of castanets, both loudest of all, drowning out all the rest, were the latest musical-box hits, the titillating can-can music, which Orpheus never knew and was never heard by the fair Helen, even the wheelbarrow would have to dance on its single wheel if it was able to dance. The Dryad danced, floated, flew, changing colour like the hummingbird in sunlight, each house and the world inside it causing reflections.

Like the gleaming lotus flower, torn from its root, is borne away by the currents and its swirling waters, she drifted off, and whenever she stopped, she was a new figure every time, so no one was able to follow, recognise and observe her.

Like cloud-pictures everything flew past her, face to face, but she did not recognise a single one of them, she did not see any image from her own home area. In her mind she saw two sparkling eyes: she thought of Mari, poor Mari! the ragged, happy girl with the red flower in her black hair. She was in the world city, rich, radiant, as when she drove past the priest’s house, the Dryad’s tree and the old oak.

She was certainly here in this deafening noise, perhaps she had just alighted from the pausing, splendid coach; magnificent carriages were standing here with liveried coachmen and silk-stockinged servants. The distinguished persons who got out were all women, richly dressed ladies. They went in through the open wrought-iron gates up the high, broad flights of steps that led to a building with marble-white columns. Perhaps this was the ‘Wonder of the World’. It was sure to be Mari!

‘Sancta Maria!’ they sang inside, the smell of incense billowed out from beneath the high, painted and gilded arches steeped in semi-obscurity.

It was l’Église Sainte-Madeleine.

Dressed in black, in the most expensive materials, sewn in the very latest and highest fashion, the distinguished female world glided over the gleaming floor. Coats of arms were embossed on the silver clasps of the velvet-bound prayer book and on the liberally scented fine handkerchief fringed with costly Brussels lace. Some of the women knelt in silent prayer in front of the altar, others sought the confessionals.

The Dryad felt an inner unrest, an anxiety, as if she had entered a place she dared not enter. Here was the home of silence, the great hall of secrets; everything was whispered and silently confided.

The Dryad saw she was clad in silk and a veil and now resembled the women of wealth and high birth; perhaps each of them was a child of longing like herself?

A sigh was heaved, so painfully profound; did it come from the corner of the confessional or from the Dryad’s own breast? She drew the veil tighter around her. She was breathing in church incense and not fresh air. This was not the place for which she was longing.

Away! away, in a restless flight! The May fly knows no rest, its flight is its life.

She was once more outside under gleaming gas candelabra with magnificent fountains. ‘All the streaming water will never be able to wash away the innocent blood that has been spilt here.’

Those words were spoken.

Here strangers stood who spoke loudly and energetically, as no one had dared to in the great hall of secrets the Dryad had just come from.

A large stone slab was turned, lifted; she didn’t understand it; she saw an open descent into the bowels of the earth; there they went down from the starry sky, from the sun-radiant gas-flames, from all that was alive.

‘I’m afraid of it!’ one of the women standing there said; ‘I daren’t go down! nor do I want to see all the splendour down there! stay with me!’

‘And return home,’ the man said, return from Paris without having seen the most remarkable thing, the real Wonder of the Present, that came into existence as the result of a single’s man’s shrewdness and will-power!’

‘I’m not going down there,’ was the answer.

‘The Wonder of the Present,’ was what had been said. The Dryad heard it, understood it; the goal for her greatest longing had been attained, and here was the entrance, down into the depths, beneath Paris; she hadn’t thought of that, but now she heard it, saw the strangers go down, and she followed them.

The staircase was of cast iron, shaped like a thread of a screw, broad and comfortable. One lamp gleamed down there and further down another one.

They stood in a maze of never-ending long intersecting halls and passages: all of the streets and alleyways of Paris could be seen here, like a dull mirror image, the names could be read, each house above had its number here, its root that stuck downwards beneath the empty, macadamised pavements, as if squeezing round a wide canal with an advancing mass of sludge. The fresh running water was led higher up in aqueducts, and highest of all, hanging like a sagging net, were gas pipes, telegraph wires. Lamps gleamed at intervals, like reflected images from the world metropolis up above. From time to time a thunderous rumbling could be heard up there, it was the heavy wagons trundling over the manhole covers.

Where was the Dryad?

You have heard about the catacombs, they are only transient parts of this new underground world, the Wonder of the Present: the sewers beneath Paris. Here stood the Dryad and not out at the World Exposition on the Champ de Mars.

She heard exclamations of amazement, admiration and approval.

‘From down here,’ it was said, come health and long life to thousands and thousands up there! our age is that of progress with all its blessings.’

That was the opinion of the humans, what the humans said, but not that of the creatures who built, lived and were born here, the rats; they squeaked from the crack in a section of old brickwork, so audibly, so clearly and so comprehensibly to the Dryad.

A large old he-rat, with a bitten-off tail, squeaked piercingly his sense of unease, oppression of spirit and his only correct opinion, and his family agreed with his every word.

‘I find that miauwing, that human miauwing, that ignorant talk quite nauseating! Oh, how fine everything now is with gas and paraffin oil! I don’t swallow that sort of thing. Everything has become so fine and so bright here that one is ashamed of oneself without knowing why. If only we lived in the age of tallow candles! it is not long since past! That was a Romantic age, as it was called.’

‘What was that you are saying!’ the Dryad asked. ‘I didn’t see you before. What are you talking about?’

‘The good old days!’ the rat said, ‘the wonderful age of great-grandfather and great-grandmother rat! back then it was a great adventure to come down here. It was a rat’s nest that was quite different from the rest of Paris! The Plague Mother lived down here; she killed humans, but never rats. Robbers and smugglers breathed freely down here. This was a place for the most fascinating personalities, such as one can only see nowadays at theatres of melodrama up above. The age of Romanticism is also past in our rat’s nest; we have got fresh air down here and paraffin oil.’

So did the rat squeak! squeaked against the new age, in honour of the old one with the Plague Mother.

A carriage stood waiting, a kind of open omnibus, with small, swift horses up front; the party got on board, set off along Boulevard Sebastopol, the one underground, right above them stretched the well-known crowded one in Paris.

The carriage disappeared into the semi-obscurity, the Dryad disappeared, lifted up into the gleaming of the gas-flames in the fresh open air; up there, and not down here in the intersecting vaults and their subdued lighting the Wonder could be found, the Wonder of the World, that which she was seeking in her short night of life; it must gleam more brightly that all the gas-flames up here, brighter than the moon which now glided out.

Yes indeed! and she saw it over there, it gleamed in front of her, it sparkled, twinkled, like the star of Venus in the heavens.

She saw a gleaming doorway that opened onto a small garden, full of light and dance melodies. Gas lights shone there like a verge around small still lakes and ponds, where water plants, artificial ones, cut out of tin sheets, formed and painted, were resplendent in all that lighting and flung the jet of water high into the air from their calyxes. Lovely weeping willows, real spring weeping willows lowered their fresh branches like a green, transparent and yet concealing veil. Here among the shrubs a bonfire was burning, its red gleam lit up small, murky, silent bowers, shot through with notes, a music that caught the ear, charming, enticing, chasing the blood through human limbs.

She saw young women, beautiful, in party dress, with the smile of innocence, the light, laughing mind of youth, a ‘Mari’, with a rose in her hair, but without a coach and jockey. How they surged, how they swirled in wild dances! what was up, what was down? As if bitten by the Tarantella they leapt, they laughed, they smiled, blissfully happy in their embrace of the entire world.

The Dryad felt herself caught up in the dance. The silk dancing shoe sat tight round her fine, little foot, chestnut-brown, like the ribbon that fluttered from her hair down over her bare shoulder. The silk-green dress billowed in large folds, but did not conceal the perfectly formed leg with the dainty foot that seemed to want to write a magic circle in the air in front of the dancing young man’s head.

Was she now in Armida’s enchanted garden? What was the place called? The name gleamed outside in gas flames:

‘Mabile’.

Music and clapping, rockets and purling waters mingled with the popping of champagne corks in here. The dancing was bacchanalian and wild, and over all of this sailed the moon, a little lopsided perhaps. The sky was cloudless, clear and pure, one seemed to look into the heavens from Mabile.

A consuming, tingling zest for life quivered through the Dryad, it was like a rush of opium.

Her eyes spoke, her lips spoke, but the words could not be heard above the sound of flutes and violins. Her dancing partner whispered words in her ear, they surged to the rhythm of the can-can; she did not understand them, we do not understand them. He stretched his arms out towards her, around her, and all he embraced was transparent, gas-filled air.

The Dryad was borne by the airstream, like the wind bears a rose petal. High up in front of her she saw a flame, a blinking flame, high up on a tower. The lighthouse shone from the goal of her longing, shone from the red lighthouse on the ‘fata morgana’ of the Champ de Mars, and to this she was borne on the spring wind. She circled the tower; the workers thought it was a butterfly they saw descending, only to die in its far too early arrival.

The moon shone, the gas flame and lanterns shone in the great halls and in the ‘buildings of the whole world’ scattered around, shone over the heights of the lawns and the rock faces so ingeniously constructed by human hands, where the waterfalls cascaded down with the force of ‘Master Bloodless’. The caves of the bottomless ocean and the depths of fresh water, the realm of the fishes opened up here, one was at the bottom of the deep pool, one was down in the sea in a glass diving bell. The water pressed against the thick glass walls around and above. Polyps, fathoms long, pliant, twisting like eels, quivering, living intestines, arms, caught hold, raised themselves up, latched themselves onto the sea bed.

A large and pensive flounder lay close by, spread itself out with great pleasure and at great leisure; the crab crawled like a huge spider over it, while the shrimps shot off with a speed, a haste, as if they were the moths and butterflies of the sea.

In the fresh water lilies grew, reeds and flowering rushes. The goldfish had lined up in ranks like red cows in a field, all with their heads in the same direction so that the current could flow straight into their jaws. Plump, portly tench gaped with their stupid eyes against the glass walls; they knew that they were at the Paris Exposition; they knew that in barrels full of water they had made the quite arduous journey here, had felt landsick when on the railway, just as humans feel seasick on the sea. They had come to see the exposition, and saw it from their own freshwater or seawater box at the theatre, saw the teeming crowds of people that moved past from morning to evening. Countries from all over the world had sent and exhibited their humans, so that the old tench and bream, the nimble perch and moss-covered carp could see these creatures and express their considered opinion about such beings.

‘It is a scaly creature!’ a muddy small roach said. ‘They change scales twice, three times a day, and make noises with their mouths, it’s called speech. We don’t change and communicate in an easier way: move the corners of our mouths and stare with our eyes! We’re far in advance of humans!’

‘But they’ve learnt how to swim,’ a little freshwater fish said; ‘I am from the large inland lake; when the weather is hot, human go into the water, but first they descale themselves, then they swim. The frogs have taught them how to, they kick with their rear legs and row with the front ones, they can’t keep it up for long. They want to resemble us, but can’t manage it! Poor humans!

And the fish stared; they thought that the whole teeming mass of humans they had seen in the strong daylight was still moving here; indeed, they were convinced they were seeing the same figures that, so to speak, had first struck their nerves of perception.

A small perch, with a beautifully tiger-striped skin and enviably round back, assured them that the ‘human mire’ was still there, he could see it.

‘I can see it too, see it oh so clearly!’ a jaundice-yellow tench said, ‘I can clearly see the lovely, shapely human figure, ‘high-boned lady’ or whatever it was they called her, she had our shaped mouth and staring eyes, two balloons at the back and a folded umbrella at the front, a large duckweed appendage, dingling and dangling. She should take all of it off, go around like we do, as first created, and then she would be a decent-looking tench, to the extent humans are able to.’

‘What became of him, the one on a line, the he-human they were pulling?’

‘He was riding in a sedan chair, sitting there with paper, ink and pen, writing everything up, writing everything down. What did he stand for? they called him a writer!’

‘He’s still riding!’ said a moss-covered young crucian carp with terrible trouble in her gullet that made her completely hoarse; she had once swallowed a hook and was still swimming around patiently with it in her throat.

‘Writer,’ she said, ‘expressed in fishy, understandable terms is a kind of octopus among humans.’

So did the fish talk in their own way. But in the middle of this artificially made, water-filled cave the sound of the workers’ hammer blows and singing could be heard, they had to work at nights too so that everything could soon be completed. They sang in the Dryad’s summernight’s dream, she herself stood in here only to fly off and disappear once more.

‘They are goldfish!’ she said, nodding to them. ‘So I got to see you even so! yes, I know you! I have known you for a long time! The swallow has talked to me about you back home. How beautiful, gleaming, lovely you are! I could kiss you, each and every one! I also know the others! that is the plump crucian for sure, that one the exquisite bream and here are the old moss-covered carp! I know you! You do not know me.’

The fish stared, they did not understand a single world, they peered out into the half-light.

The Dryad was no longer there, she was out in the open air, where the world’s ‘Wonder Flower’ exuded its scent from the various lands, from the land of ryebread, the coast of split cod, the realm of Russia leather, the river bank of eau de cologne and the Orient of rose-oil.

When, after a night at the ball, we ride home half-awake, we can still make out the melodies we have heard running through our ears, we could sing each and every one of them. And just as in the eye of the slain person the last visual impression remains there photographically for a while, so too here in the night there was the bustle and gleaming of life in the daytime, it had not faded away, not been extinguished; the Dryad sensed it, and knew: that is how it will continue to sound, the following day too.

The Dryad stood among the fragrant roses, thought she knew them from her native soil. Roses from the castle park and the priest’s garden. She also saw the red pomegranate flower here too; such a one Mari had worn in her jet-black hair.

Memories from her childhood home out in the country flickered in her thoughts, the spectacle around her she drank in with eager eyes, while the feverish unrest filled her, led her through the wonderful halls.

She felt tired and this tiredness increased. She felt an urge to rest on the soft expanse of oriental cushions and rugs in here, or to lean down along with the weeping willow towards the clear water and dip herself in it.

But the May fly knows no rest. In a few minutes her allotted time would come to an end.

Her thoughts quivered, her limbs quivered, she collapsed onto the grass by the purling water.

‘You spring up from the earth with lasting life!’ she said, ‘slake my thirst, grant me refreshment!’

‘I am not a living spring!’ the water replied. ‘Machinery causes me to rise.’

‘Give me all your freshness, green grass,’ the Dryad begged. ‘Give me one of your fragrant flowers!’

‘We die if we are pulled up!’ said the blades of grass and the flowers.

‘Kiss me, you fresh current of air! Just one kiss of life!’

‘Soon the sun will kiss the clouds red!’ the wind said, ‘and then you will be among the dead, departed, just as all splendour here departs before the year is over, and I can once more play with the light, loose sand on the square here, blow dust over the earth, dust into the air, dust! All is just dust!’

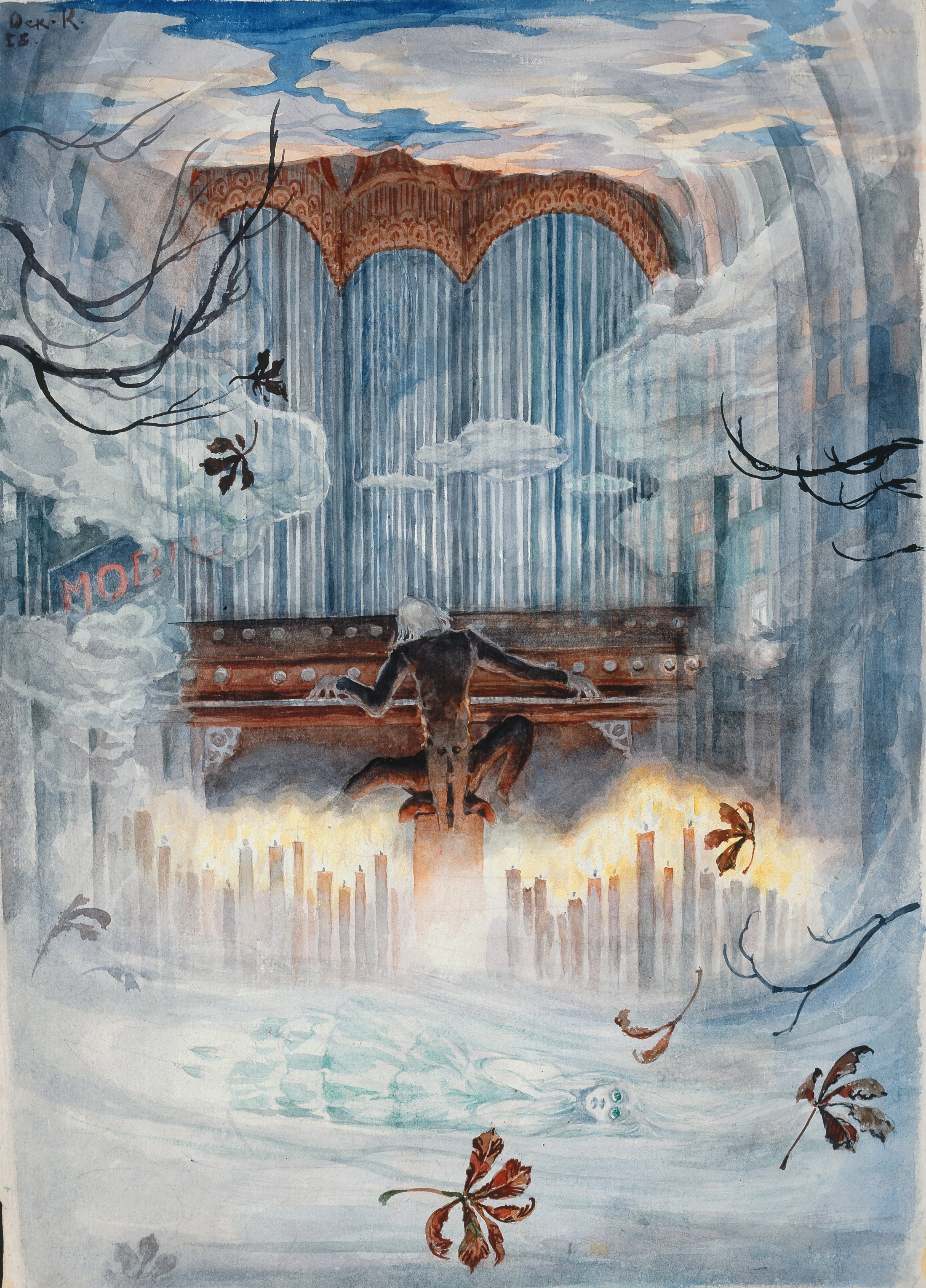

The Dryad felt an anxiety like that of the woman who has slashed her wrist in the bath and is bleeding to death, but as she bleeds still wants to live. She raised herself up, took a few steps forward and then sank to the ground once more in front of a small church. The door was open, candles were burning at the altar, the organ was playing.

What music! such strains the Dryad had never heard before, and yet in them she seemed to hear well-known voices. They came from the inner heart of all creation. She seemed to sense the soughing of the old oak tree, she seemed to hear the old priest talk of heroic deeds, of famous names, of what God’s creation was able to grant as a gift to a coming age, had to give in order to gain future life for itself.

The strains of the organ swelled and sounded, spoke in a song:

‘Your longing and desire pulled you up by the roots from your God-given place. That became the ruin of you, poor Dryad!’

The strains of the organ, soft, gentle, sounded like weeping, died away like weeping.

In the sky the clouds gleamed red. The wind blew and sang: ‘Depart, you who are dead, now the sun is rising!’

The first rays fell onto the Dryad. Her form gleamed in changing colours, like the soap bubble when it bursts, disappears and becomes a droplet, a tear, that falls to the earth and disappears.

Poor Dryad! a drop of dew, just a tear, wept and then swept away!

The sun shone over the ‘fata morgana’ of the Champ de Mars, shone over the entire metropolis of Paris, over the small square with trees and the plashing fountain, between the tall houses where the chestnut tree stood, but with drooping branches, withered leaves, the tree that only the day before stretched up as full of life as spring itself. Now it was withered, people said, the Dryad was lifeless, had wafted away like a cloud, no one knows where.

On the ground there lay a withered, broken chestnut blossom, the church’s holy water was unable to call it back to life. Before long it was trampled underfoot in the dust.

All of this has taken place and been experienced.

We saw it ourselves during the Paris Exposition in 1867, in our own age, in the great, wonderful age of the fairy tale.

Del

Henvis til værket

Hans Christian Andersen: The Dryad. Translated by John Irons, edited by , published by The Hans Christian Andersen Centre, University of Southern Denmark, Odense. Version 1.0. Published 2024-04-01[INFO OM 18-binds-udgaven 2003-2009...] for Det Danske Sprog- og Litteraturselskab. Digitaliseret af Holger Berg til sitet hcandersen.dk

Creative Commons, BY-NC-SA